By John Berry

The Cessna 206 float plane ground monotonously on and the bank of cloud that had barred our way through Centre Pass, to Manapouri, finally slipped below the engine cowl. However our pilot still didn’t relax; urgent murmurings into his microphone were being answered by equally urgent but, to me, unintelligible static from our companion aircraft. Something was definitely up!

He had been almost lifting the Cessna physically as we flew up the Seaforth River, at the close of our fortnight, looking for the elusive remnants of the New Zealand Moose herd, in the area around Dusky Sound on the South-West coast of the South island of New Zealand.

Colin James, who had accompanied me on the jaunt, was still perfectly relaxed through all this. He had been too busy looking for and identifying the places we had been in the preceding two weeks, to notice the tension in our pilot. “Gair Loch” he shouted, leaning back towards me, finger stabbing downwards towards a patch of

water in the green tangled mass of bush below.

“What’s wrong? You don’t look too good” said Colin. I just pointed to the fuel gauge in the dash of the Cessna. I had just sorted it out from the jumble of other instruments on the board and wished I hadn’t. The needle was firmly fixed on “E” – Empty! It takes a bit to shake Colin, an experienced bushman, with a reputation for good judgement, which had made him the top advisor to the NZ Police on Search and Rescue around our area, but that shook him. He recovered enough to mutter something about “plenty in the other tank”, only to be informed, by a very agitated

pilot, that the “other tank” was emptied on the way in to pick us up. The situation we were in was due to that eternal enemy of the stalker and climber

in New Zealand high country – the weather. Five days of perfect weather in the latter part of our stay at Dusky Soun d, had given way to a typical Fiordland day when we were due to leave. Rain born on the Nor-West winds rolled in off the Tasman Sea and that, along with the fog had stopped any chance of flying at the appointed time. The following day proved little better, until late in the afternoon, when the rain abated and the mists lifted on a slight Sou-West change. Almost at the same moment as the fog disappeared back towards the sea, passed islands and coves named by Captain Cook, on his voyages to this place, the blue and white Cessna arrived.

d, had given way to a typical Fiordland day when we were due to leave. Rain born on the Nor-West winds rolled in off the Tasman Sea and that, along with the fog had stopped any chance of flying at the appointed time. The following day proved little better, until late in the afternoon, when the rain abated and the mists lifted on a slight Sou-West change. Almost at the same moment as the fog disappeared back towards the sea, passed islands and coves named by Captain Cook, on his voyages to this place, the blue and white Cessna arrived.

A scramble of gear to the beach at Supper Cove hut, followed by shouted farewells, to those left behind to

carry on with the search, had left us breathless. It had been pleasant to sit back and watch the rugged terrain, laced with swamps and mud, slip under the wings and reflect on this trip, which begun in its planning many months before – now it looked like ending in disaster.

My initial interest in Dusky Sound and the New Zealand moose herd, had begun some years before this

seemingly ill-fated flight. I think that dank corner of New Zealand, known as “Fiordland” holds a fascination for all New Zealand hunters.Once visited, it draws then back, time and time again, despite rain, fog and insects;

so it had been for me. The thought of a few moose, hanging on in an unknown creek, or living in a hidden swamp, appealed to me, so when the chance came to join the Forest Service survey of the ”Moose Area”, I jumped at it.

The Forest Service had been commissioned to do the survey following a newspaper report of a professional venison hunter shooting a Moose in one of the creeks leading into Dusky Sound. Much public comment was generated by this report and the Fiordland National Park Board, after suggestions from the NZDA banned the shooting of moose. (Prior to that no mention of moose was made on the hunting permits for the area, so it was legal to shoot them).

The survey was under the leadership of Ken Tustin*, a scientist with the Forest and Range Experiment Station based outside of Christchurch, Ken had had experience with moose in Canada whilst studying there. He proved to be an ideal leader, for what was to be a monumental task. Keen, efficient and irrepressibly cheerful, he tackled the task of putting six to ten men into one of the remotest areas of Australasia for a period of fourteen weeks, with the thoroughness of a scientist and the keenness and forethought of a first class hunter/bushman.

Ken’s initial effort was to gather information on the history of the herd. This uncovered some most interesting facts and it became obvious that there had been much more contact between people and the animal than was generally recognised. The first liberation had been in the Hokitika Valley, on the West Coast near the town of the same name, this liberation of two bulls and a cow failed.

The second liberation was at Supper Cove, Dusky Sound in 1910. The ten animals, four bulls and six cows, originated from Saskatchewan Canada. They appeared to successfully colonize the Seaforth River and several creeks leading into the Supper Cove and Wet Jacket Arm areas of Dusky Sound.

*Ken Tustin wrote one of the definitive studies on Tahr in NZ, then pursued a career as a helicopter pilot. He has spent many years continuing the search for moose, placing cameras in the area and spending weeks looking for sign.

Following a Government report of 1921, licences were issued for the legal hunting

of Bull Moose in 1923. At this time the animals appeared to be building up in

numbers satisfactorily, although they never reached large numbers.

The moose of Dusky proved to be an elusive target for the hunters of the time; it was not until 1929 that a bull was taken legally. This bull was shot by E.J. Herrick, on a clearing in the Seaforth River, now known as “Herrick’s Clearing”. Herrick is the only man known to have taken two moose from the New Zealand herd, his second bull was shot in 1934, in a creek, also bearing his name, which falls into Wet Jacket Arm.

Moose had been photographed prior to Herrick’s securing one, by Les Mirwell and Jack Templeton, when they photographed two bulls on a sand bar in the Seaforth around the Loch Marie area in 1929. It was though that Herrick’s bull may have been one of these. Robin Francis-Smith also secured photos. This time of a cow browsing in Herrick’s creek during the second of his three visits in 1950, 51 and 52. He also shot a cow on his 1952 trip.

During1952/53 Francis-Smith was accompanied by Percy Lyes and Max Curtis, both well-known hunters of that time. Lyes, who already had the New Zealand record for length for Red Stag, took the third bull shot legally in New Zealand. This also fell in Herrick’s Creek. Ken’s research however, showed that many more than these had been taken. As he explained around various camp fires, during the previous fortnight, the history of the herd is wrapped in rumour and tales of “Someone who knew someone else, who saw one once”. Obviously many of the leads proved worthless, but some had substance and from these he ascertained that the herd had spread to islands, coves and valleys far from the original site of liberation.

Resolution Island, Cascade Cove, Fanny Bay, Shark Cove, Acheron Passage, Nine- Fathom Passage, Oke Island and many other place names flitted into our camp side discussions, as we talked about these fascinating and elusive animals. The search rapidly became a history lesson for all those involved in expedition, as we visited these places and many others named by Captain Cook and his men, during their time at Dusky. The site from which Cook observed the transit of Venus was located and the stumps of trees cleared for this observation and to repair his ship, could still be seen. Other evidence of long dead settlers can still be found at other sites.

Crumbling stone foundations at Dougherty’s Beach are all that is left to testify to this man’s struggle to live, whilst mining at Shark Cove. Although the mine is supposed to be still locatable, I did not look for it. One can only wonder why he chose to live and work at sites some miles apart, his

only transport being a row boat. Could it have been gold in the creek behind his cabin that kept him there year after year?

Richard Henry struggled, single handed, for years collecting flightless birds, Kiwis and Kakapo, taking them to Resolution Island, where he hoped they would escape the attentions of the stoats and rats, that invaded the area after the turn of the century. He failed and left over ten years of work behind, when he found traces of birds killed by stoats that had floated across Acheron Passage to Resolution. The story of “too little, too late” is one that often occurs in the aid given to New Zealand’s unique animal life – both native and introduced. Often it was the historical interest of the area that provided the only incentive to

keep us going day after day, through thigh deep mud, and usually continuous rain. It became normal, during fly camps, to wake up damp, spend all day soaking and go to bed wet, looking forward to waking up to only damp, in the morning.

The search had been in progress for some two weeks before Colin and I joined it. During this time it had been concentrated on the Wet Jacket Arm area, including Herrick’s Creek. This area had been picked for the first period, because most of the sightings investigated pointed towards this area being the most likely in which to locate a moose.

Herrick’s Creek seems to have several features which make it attractive to moose. Firstly there are extensive areas of seral vegetation – ‘The Greens’ as they are known by experienced hunters in Fiordland. These patches provide much favoured browse vegetation for both moose and red deer. They are readily recognised by their light green colouration, which stands out against the dark bulk of the bush. (This fact should be remembered by anyone contemplating a Wapiti or Red Deer trip into the Fiordland area).

Secondly, Herrick’s Creek flows through a small lake, several reports mentioned seeing signs in or around this lake. It seems that, the known habit of water feeding on aquatic plants, common in their native Canada, leads New Zealand moose to frequent this lake in search of similar aquatic weeds.

The third factor, which may not be so obvious, is that Herrick’s Creek and Moose Creek, which flows to the Seaforth River, form a route, by way of a low bush saddle, between the two catchments of Wet Jacket and Supper Cove. It seems likely that the shy moose, when disturbed may slip away, unseen, completely out of the area being hunted and take up residence in a completely new catchment. Ample evidence of their ability to away, without being seen or heard was forthcoming later in the expedition, when a moose, probably a cow, played hide and seek, in a confined area for several days, despite the attentions of several expert bush hunters.

Unfortunately the results of fourteen days of intensive work had shown that theories worked out on maps, in the comfort of civilization are not binding on moose in the wild. The faces of the party that greeted our arrival at Supper Cove, told us of their lack of success, as well as the rigours that we were to experience.

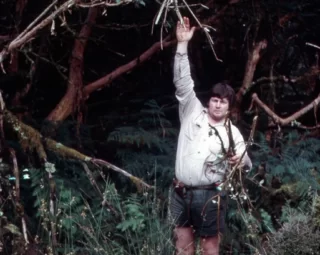

Whenever I get to new country, I can’t wait to get out and have a look about and so it proved on this occasion. Neither Colin nor I were content to wait for the next morning to start as Ken suggested. We decided to fill the day with a jaunt into a small creek immediately behind the Supper Cove Base hut.

This sortie quickly highlighted the difficulty of the task ahead. The bush, like everyone’s idea of a tropical jungle, hangs in vines, moss and fungi, whilst the floor slops underfoot. The difficulties of tracking and sighting a small population of moose were made even worse by ever present red deer moving along in front of us.

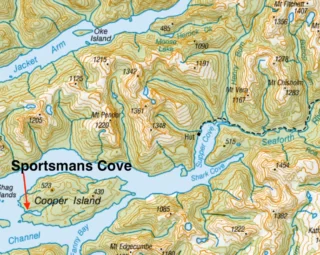

Excitement and enthusiasm proved an inefficient raincoat the next morning, during the three hour ride in our three metre aluminium outboard. Typical inch-an-hour rain kept the sea flat, but soaked us and our gear, until at one stage we

contemplated having to bail the collected water from the boat. Our destination was Sportsman’s Cove on Cooper Island, one of a series of supply dumps, previously provisioned by fishing boat.

Sportsman’s Cove

at the west end of

Cooper Island.

Named by Captain

Cook due to the

boat races held

here by his crew.

On arrival at Sportsman’s, we set about making ourselves comfortable (!), a tent was quickly erected beneath a plastic fly left by the provisioning party weeks before. Wood was collected for cooking and drying fires, here the knowledge of which native timbers burn wet and green were of prime importance. Rata and Broadleaf were sorted and stacked for these features.

Once our camp was pronounced suitable by Ken, who accompanied Colin and I during this period, we set about the task of catching and preparing our first truly, ‘Dusky Sound’ meal, ten short minutes fishing supplied six or seven large Blue Cod and several six or seven kilo Groper. A belly bulging with freshly poached Groper fillets does wonders for one’s idea of paradise, even when crawling into a wet sleeping bag!

Once our camp was pronounced suitable by Ken, who accompanied Colin and I during this period, we set about the task of catching and preparing our first truly, ‘Dusky Sound’ meal, ten short minutes fishing supplied six or seven large Blue Cod and several six or seven kilo Groper. A belly bulging with freshly poached Groper fillets does wonders for one’s idea of paradise, even when crawling into a wet sleeping bag!

The next five days were spent in a fairly leisurely survey of Cooper Island, the small islands around the area and the faces of the mainland adjoining Acheron Passage and Dusky Sound proper. Several times ‘sign’ was found, but each time it was discarded as possibly caused by something other than a moose. We wanted irrefutable evidence, fresh high,

(over two metres), browse, footprints over 110 mms long, or something similar.

Later much of this sign was reappraised, when fresh sign was found, and it was felt

to be legitimate evidence left from previous seasons. Due to the nature of the

Dusky area the chances of stumbling on a moose in the open is unlikely, most of our time was spent looking for signs that an animal was frequenting an area. It was then hoped that by saturating the area with hunters a sighting would be made.

On our return from Sportsman’s to Supper Cove base, we were confronted by a hastily scribbled note, saying that the others, who had travelled up the Seaforth River, had found what they believed to be good sign in the vicinity of the Loch Marie hut. The decision was unanimous – Loch Marie for us!

The walk from Supper Cove to Loch Marie is a pleasant stroll along a track built in 1903. During this period of exceptional Government interest in the New Zealand back country, many such tracks were installed, the Supper Cove / Lake Manapouri track being one of the most ambitious. The difficulties of terrain and weather proved too much for even that tough era, the forming of the track was eventually abandoned several miles short of its ultimate destination.

One can but wonder today at the human effort expended in forcing a way several kilometres up the Seaforth, over bluffs and through swamps, without the benefit of machinery, all done with picks, shovels and wheel barrows accompanied by sandflies galore, blood, sweat, rain and lots of colourful language.

The walk to Loch Marie took us into the heart of the Dusky deer population. To sight thirty deer in a couple of hours walk was not uncommon and the sight of deer grazing on the river flats around the Loch Marie hut became common place.

Obviously any young moose, newly weaned and of a similar size to an adult red deer is in for a hard time gathering food in competition with these animals. The Red deer must pose the single greatest threat to the survival of moose and probably their more aggressive colonization and rapid build-up were responsible for the continually low moose population.  The sign that had sent us poste-haste to Loch Marie was a shovel full of large droppings found on the flats some distance up the Seaforth from the hut. These flats and other areas in the Seaforth proved productive of sign. Before the end of the expedition high browse

The sign that had sent us poste-haste to Loch Marie was a shovel full of large droppings found on the flats some distance up the Seaforth from the hut. These flats and other areas in the Seaforth proved productive of sign. Before the end of the expedition high browse

was located in the upper and lower Seaforth, and two creeks leading into the upper

part of the catchment. Colin and I found an indistinct set of hoof prints in another catchment, the Roa, these prints were old and washed by the rain but appeared much too large for those of a red deer. Additionally a set of fresh prints showed the existence of an animal near the mouth of the Seaforth at Supper Cove.

Loch Marie is blessed with the highest population of sand-flies I know of, an area where the wearing of insect repellent becomes second nature. To stop for more than a few seconds means that you are descended upon by a black cloud of blood sucking flies. Any venture beyond the confines of the hut commits you to the ritualistic application of neat dimethylthalate and the call of nature is accompanied by prolonged blasts on an aerosol bug-bomb.

Having spent several days in the area, Ken decided that he needed a ‘holiday’ and

felt that that a few days above the bush line at a lake, which he had visited years before on another survey, was called for. His description of a few hours climb decided me that I would carry on fighting sand-flies at a lower level. Hours of panting along in his wake, on relatively flat walks had shown me that his physical capabilities were far in excess of mine. (Some weeks later I met Ken in Te Anau, as I was preparing for a Wapiti hunt in the Worsely River, he had walked out from Supper Cove to Lake Manapouri in a single twelve hour burst, normally this is considered a four day tramp.)

Ken’s departure allowed Colin and myself to continue a systematic search of the lower Seaforth, below Loch Marie. Working alternatively from the Loch Marie hut, the Supper Cove base and a fly camp half way between, we did a detailed search of the bush and swamps bordering the river.

A search of the true left bank failed to uncover any sign of a bull reportedly observed there the previous year by another NZDA party, but it did uncover the existence of a large, previously unknown clearing. Just the sort of place where a moose could happily exist while people walk past only a few hundred metres

away on the other side of a normally unfordable river.

Red deer were still numerous throughout this area, despite the attentions of Russell Dawson, a well-known professional hunter from Te Anau, their sign being so thick in places as to make ground tracking of individual animals impossible. Russell’s feats of shooting and carrying continually amazed me, he was the only man I knew of who could confidently shoot five deer from a mob in dense bush, with as many shots from a bolt action .243. Shooting in this area was however the easy part, once the deer is grounded the back breaking task of recovery begins. To move deer carcases over rough terrain, single handed day after day, with no mechanical aids, requires a pretty tough sort of character.

Since the by-laws of the National Park outlaw the use of refrigerated coolers in the park, the business of meat hunting becomes a game of chance. A plane load of carcases had to be assembled at a pickup point as quickly as possible, then the plane ordered by radio with a race between weather, plane and purification begins – often the later wins.

Late one evening as we prepared a meal on a small fire built into the water table beside the Seaforth track, Colin remarked that we had better move down river the next day as we were nearing the date of our pickup. So our adventure at Dusky Sound was to draw to a close, but the opening scenes of the flight back to Te Anau were still to come.

If anything, the bleak outlook of our flight looked even bleaker, as we levelled off over Centre Pass,  now completely hidden in dense cloud.

now completely hidden in dense cloud.

The cloud extended unbroken as far to the East as we could see.

“A hole, I need a bloody hole to get down through. Keep looking for one and watch the other plane” our pilot commanded. Now almost beside himself as we zigzagged across the

sky. He may have needed one, I desired one. If I’d been a religious person no doubt I would have prayed for one. Whether or not praying helps, I don’t know, but a clatter of static from the radio, turned our attention to our companion aircraft diving into a gap in the cloud.

Seconds later we descended, power off through the layer of cloud to see Manapouri

directly below, thirty odd kilometres from home.

As Te Anau appeared in the distance, a sense of relief relaxed all those in the Cessna. The pilot relaxed and announced his capability of being able to glide home from “about here”.

There was no greeting circuits of the town this trip, just a long steady straight approach with minimum power until the hiss of water on the floats and twin plumes of spray behind the tail plane signified the end to my quest for the elusive New Zealand Moose!

FOOT NOTE:

The year after I spent my time in Dusky, Colin James and

The year after I spent my time in Dusky, Colin James and

two of his mates returned to Supper Cove, (yes, it gets to

you)! They found positive sign, clear, fresh hoof prints of a

moose – probably a cow, at the mouth of the Henry Burn

(Moose Creek), plus fresh high browse.

I am indebted to Colin and Eddie Clark, who were kind

enough to give me photos of this evidence.

The NZDA also mounted a further survey of the Seaforth

area, but unfortunately no further evidence of moose was

found as far as I know.

Ken Tustin has continued to search, but has never

managed a positive sighting, even though he has had several game cameras operating.

(Correction – Ken did get a photo of a Moose in 1995 in Herrick Creek, although a little indistinct. Some dispute it but those who have seen Moose, have no doubt what it is! See below! Editor)

The mystery, myth, legend remains.

John Berry 2019